THE TAKE AWAY

Martin and Zimmerman: of Justice and Mercy

By Kersley Fitzgerald

We don't know anything about each other.

The most referenced post I've seen has to be Christena Cleveland's article on privilege. Christena, a social psychologist and a believer, talks about the long-standing issue of racial profiling in this country. How an African American man's interaction with the police is so completely different than a white man's. And how no matter how often the African American man brings the subject up, the white man blows him off.

But then she goes on to say it's not just about race (ethnicity). It's about privilege. How we view everything from the trial to politics to civil authorities is influenced by not only our ethnicity, but our socio-economic status, our education, our health, our attractiveness, and our gender [1]. And it usually doesn't occur to those of us who are privileged that other people may be having a different experience. She points out:

So if a socio-economically oppressed black woman complains to me that people are always attributing her behavior to her "uncivilized" social class, I'm tempted to respond by saying to her, "Are you sure you aren't overreacting?" or by thinking to myself "That hasn't happened to me, so I don't think it has really happened to her." [2]Which is poignant because Christena is, herself, African American—but privileged by her education, her social status, and her economic status.

She admits that because of that privilege, she experiences life in a very different way. And then challenges both herself and others of privilege to listen to those with different stories.

And by listen to, I'm assuming she means more than just talk about how great a movie The Help is.

Victor Montalvo's article is posted in concert with Ms. Cleveland's. He speaks more about how emotional closure in these things depends so much on finding the villain and dealing with him. [3] But he also talks about the only thing that will ever make a difference.

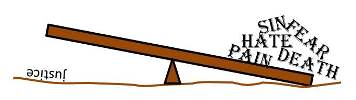

There was no way that the trial was going to bring justice. There was no justice in what happened. There were a whole lot of mistakes, a whole lot of fear, and not a little pride. On both sides. There's no way to bring Trayvon Martin back—to go back in time and sort things out. We can only move forward.

Montalvo goes one further than Cleveland. Not only should we talk to each other and listen to each other, we should live life together. He pastors a multi-ethnic congregation that has integrated worship practices of several different cultures. And that is the key: "The Church must model the way out of this racial abyss."

Why the church? Because the church is the only gathering of people who are defined and united by something bigger than ourselves. Our base is our joint relationship with Christ. Not our country of origin, not our ethnicity, and not our favorite sports team. The truest part of us is God. If we live that properly, there is nothing on earth that can usurp that.

Nothing we do now can bring justice. But if we follow Christ, it just might bring good (Romans 8:28).

My friend Alan Cross hasn't written an article yet, but he said a couple of pretty grounding things on Facebook recently. Somewhere in the center of this maelstrom of societal wrongs and talking heads and accusations and verdicts sits a family who believed their son was murdered in cold blood. Whether their perceptions were wrong or right is far less important right now than their grieving, broken hearts. There is no justice for their son. And that injustice has been declared on a very public stage.

The boss recently wrote an article on justice from God's point of view. We can't understand it. It doesn't make sense. God's justice is too filled with grace and self-sacrifice and love to be logical to our minds. And yet, we're not only called to accept it, we're called to emulate it.

That's the only justice the church can offer the Martin family right now. To say, "I have been hurt, too. Your pain is real and it matters." To set aside the social implications and just sit and mourn the fallen world together.

Jesus did this when Lazarus died (John 11). He knew that Lazarus would be resurrected and spend eternity in paradise. But He still showed that it was okay to mourn his death. The bigger picture brings clarity, but sometimes the smaller picture needs to be worked through first.

All to say that harping on who was wrong, who was right, was the verdict just—all these arguments are only going to be divisive. As Christians, we should be looking around at what others are going through, and running as hard as we can to embody Christ's love, not blame. To do otherwise is to value things of the earth over the Kingdom of God.

Only then will we have a chance at changing society, law enforcement, and the legal system to be more just to everyone.

The Good News is that Jesus came to die for both racist and non-racist sinners. Former enemies can become friends in Him, and benefit from the exact same grace. Who will step up, address this issue, and proclaim the truth? Whether or not you think race is a factor in this case, you can't deny that race is a factor in the lives of so many of us every day.triplee

[1] Reference the recent story about the Australian man named Kim who only got a job offer after he identified himself as male on his resume.

[2] For some reason, the scene from the Breakfast Club pops into my head. The bit where John cries out to Claire, "Don't you ever talk about my friends. You don't know any of my friends. You don't look at any of my friends. And you certainly wouldn't condescend to speak to any of my friends. So you just stick to the things you know: shopping, nail polish, your father's BMW, and your poor, rich drunk mother in the Caribbean."

[3] Which brings me to the quote from The American President from one presidential candidate about another: "He is interested in two things and two things only: making you afraid of it and telling you who's to blame for it."

comments powered by Disqus

Published 7-17-13